Gold nuggets of history

Historically, wotou | 窝头 were made as a cheap, filling grain and an easily-transportable unit of food for poor people in China. Spending a day working at a sweat shop? Bring a wotou! Working 15 hours in the fields? Bring two! A more refined version of them dubbed "Royal Wotou" made its way into the Imperial Palace during the early 1900's.

On a recent trip to Beijing, I went to a fancy restaurant in Beihai Park with Nainai and Erdaye—"second eldest uncle"—where I ate the cornbread-like delicacies. They were about the size of thimbles, subtly sweet and delicate. This was not the wotou of my father's childhood.

Baba grew up during the Great Leap Forward Famine, a three-year period when over 15 million Chinese people died from starvation as a result of Mao Zedong's failed economic and social campaign to modernize China. My obsession with zero food waste stems from everything my family went through during this time.

Baba remembers always being hungry—he tells the story of he and a neighbor boy arguing over 15 grains of rice. White Boyfriend was doing dishes once at my parents' house and he started to take the rice cooker pot to the sink to wash. Baba stopped him gently and grabbed a pair of chopsticks to eat the residual kernels of rice stuck to the sides of the bowl, those memories surely surfacing swiftly by rote.

Nainai tells a slightly different story—that Baba had it the easiest out of her three sons because he was the youngest. She remembers saving him an egg a day, a luxury during those tough years. I watched my uncle crack an egg during my last trip to China. He shook it vigorously before gently tapping it on the side of a bowl. He explained to me that it helped release the egg white from the shell so you can more easily get every last bit of the egg out.

The humble wotou represents the hardship of the famine and everything my family went through. Baba recalls going to work and only being able to afford wotou to eat. He became so constipated that he talks about one day running home from work because he got so excited when he was overcome with a need to go number two.

This recipe version is more of a dessert—I've added red dates and glutinous rice flour so they're sticky and sweet. While it pays homage to its predecessor, it is far more luxurious. Start by soaking your dates in water.

Chop them into small pieces, taking care to remove the inner pit of each.

Mix together the dry ingredients.

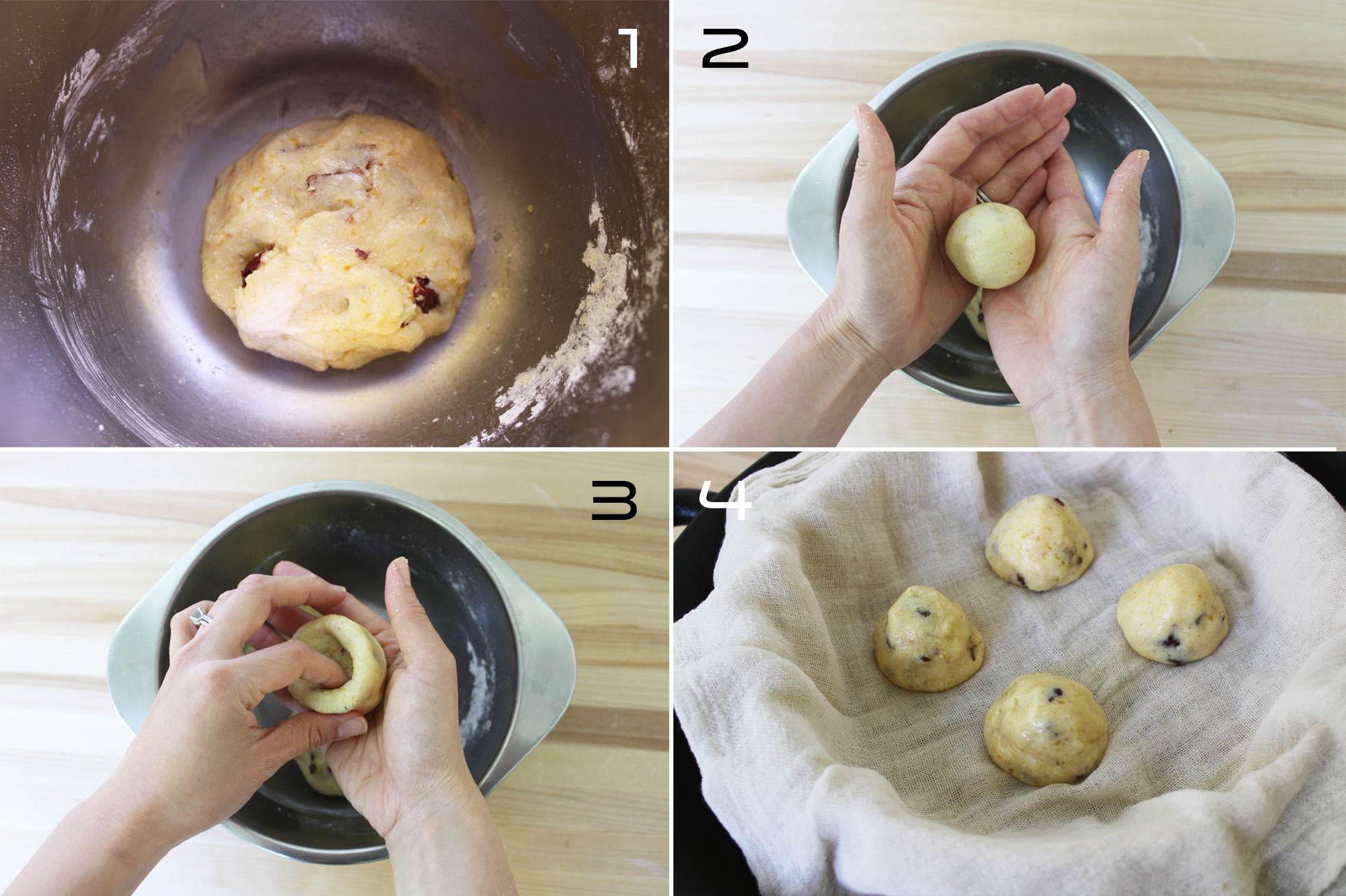

Add water and knead until a dough forms; then fold in the dates. Form the tiny cones in the palm of your hand, taking care to create a hole in the bottom.

Steam the wotou until they resemble shiny, gold nuggets worthy of emperors. But know that millions of people in China died because they weren't lucky enough to even have wotou to eat. And the next time White Boyfriend rolls his eyes when you scrape the bottom of the pot for the third time with the spatula, stay true to yourself and where you came from, and remember the people in your life who lived through the most bitter years of Chinese history.

For the straight-up Sticky Date Wotou recipe, click here.